Environments with hidden state: POMDPs

Introduction: Learning about the world from observation

The previous chapters made two strong assumptions that often fail in practice. First, we assumed the environment was an MDP, where the state is fully observed by the agent at all times. Second, we assumed that the agent starts off with full knowledge of the MDP – rather than having to learn its parameters from experience. This chapter relaxes the first assumption by introducing POMDPs. The next chapter introduces reinforcement learning, an approach to learning MDPs from experience.

POMDP Agent Model

Informal overview

In an MDP the agent observes the full state of the environment at each timestep. In Gridworld, for instance, the agent always knows their precise position and is uncertain only about their future position. Yet in real-world problems, the agent often does not observe the full state every timestep. For example, suppose you are sailing at night without any navigation instruments. You might be very uncertain about your precise position and you only learn about it indirectly, by waiting to observe certain landmarks in the distance. For environments where the state is only observed partially and indirectly, we use Partially Observed Markov Decision Processes (POMDPs).

In a Partially Observed Markov Decision Process (POMDP), the agent knows the transition function of the environment. This distinguishes POMDPs from Reinforcement Learning problems. However, the agent starts each episode uncertain about the precise state of the environment. For example, if the agent is choosing where to eat on holiday, they may be uncertain about their own location and uncertain about which restaurants are open.

The agent learns about the state indirectly via observations. At each timestep, they receive an observation that depends on the true state and their previous action (according to a fixed observation function). They update a probability distribution on the current state and then choose an action. The action causes a state transition just like in an MDP but the agent only receives indirect evidence about the new state.

As an example, consider the Restaurant Choice Problem. Suppose Bob doesn’t know whether the Noodle Shop is open. Previously, the agent’s state consisted of Bob’s location on the grid as well as the remaining time. In the POMDP case, the state also represents whether or not the Noodle Shop is open, which determines whether Bob can enter the Noodle Shop. When Bob gets close enough to the Noodle Shop, he will observe whether or not it’s open. Bob’s planning should take this into account: if the Noodle Shop is closed then Bob will observe this can simply head to a different restaurant.

Formal model

We first define the class of decision probems (POMDPs) and then define an agent model for optimally solving these problems. Our definitions are based on reft:kaelbling1998planning.

A Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP) is a tuple , where:

-

(state space), (action space), (transition function), (utility or reward function) form an MDP as defined in chapter 3.1, with assumed to be deterministic1.

-

is the finite space of observations the agent can receive.

-

is a function . This is the observation function, which maps an action and the state resulting from taking to an observation drawn from .

So at each timestep, the agent transitions from state to state (where and are generally unknown to the agent) having performed action . On entering the agent receives an observation and a utility .

To characterize the behavior of an expected-utility maximizing agent, we need to formalize the belief-updating process. Let , the current belief function, be a probability distribution over the agent’s current state. Then the agent’s succesor belief function over their next state is the result of a Bayesian update on the observation where is the agent’s action in . That is:

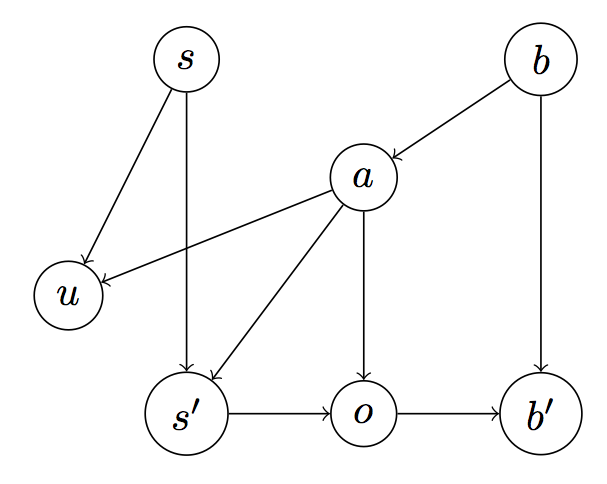

Intuitively, the probability that is the new state depends on the marginal probability of transitioning to (given ) and the probability of the observation occurring in . The relation between the variables in a POMDP is summarized in Figure 1 (below).

Figure 1: The dependency structure between variables in a POMDP.

The ordering of events in Figure 1 is as follows:

(1). The agent chooses an action based on belief distribution over their current state (which is actually ).

(2). The agent gets utility when leaving state having taken .

(3). The agent transitions to state , where it gets observation and updates its belief to by updating on the observation .

In our previous agent model for MDPs, we defined the expected utility of an action in a state recursively in terms of the expected utility of the resulting pair of state and action . This same recursive characterization of expected utility still holds. The important difference is that the agent’s action in depends on their updated belief . Hence the expected utility of in depends on the agent’s belief over the state . We call the following the POMDP Expected Utility of State Recursion. This recursion defines the function , which is analogous to the value function, , in reft:kaelbling1998planning.

POMDP Expected Utility of State Recursion:

where:

-

we have and

-

is the updated belief function on observation , as defined above

-

is the softmax action the agent takes given belief

The agent cannot use this definition to directly compute the best action, since the agent doesn’t know the state. Instead the agent takes an expectation over their belief distribution, picking the action that maximizes the following:

We can also represent the expected utility of action given belief in terms of a recursion on the successor belief state. We call this the Expected Utility of Belief Recursion, which is closely related to the Bellman Equations for POMDPs:

where , , and are distributed as in the Expected Utility of State Recursion.

Unfortunately, finding the optimal policy for POMDPs is intractable. Even in the special case where observations are deterministic and the horizon is finite, determining whether the optimal policy has expected utility greater than some constant is PSPACE-complete refp:papadimitriou1987complexity.

Implementation of the Model

As with the agent model for MDPs, we provide a direct translation of the equations above into an agent model for solving POMDPs. The variables nextState, nextObservation, nextBelief, and nextAction correspond to , , and respectively, and we use the Expected Utility of Belief Recursion.

var updateBelief = function(belief, observation, action){

return Infer({ model() {

var state = sample(belief);

var predictedNextState = transition(state, action);

var predictedObservation = observe(predictedNextState);

condition(_.isEqual(predictedObservation, observation));

return predictedNextState;

}});

};

var act = function(belief) {

return Infer({ model() {

var action = uniformDraw(actions);

var eu = expectedUtility(belief, action);

factor(alpha * eu);

return action;

}});

};

var expectedUtility = function(belief, action) {

return expectation(

Infer({ model() {

var state = sample(belief);

var u = utility(state, action);

if (state.terminateAfterAction) {

return u;

} else {

var nextState = transition(state, action);

var nextObservation = observe(nextState);

var nextBelief = updateBelief(belief, nextObservation, action);

var nextAction = sample(act(nextBelief));

return u + expectedUtility(nextBelief, nextAction);

}

}}));

};

// To simulate the agent, we need to transition

// the state, sample an observation, then

// compute agent's action (after agent has updated belief).

// *startState* is agent's actual startState (unknown to agent)

// *priorBelief* is agent's initial belief function

var simulate = function(startState, priorBelief) {

var sampleSequence = function(state, priorBelief, action) {

var observation = observe(state);

var belief = updateBelief(priorBelief, observation, action);

var action = sample(act(belief));

var output = [ [state, action] ];

if (state.terminateAfterAction){

return output;

} else {

var nextState = transition(state, action);

return output.concat(sampleSequence(nextState, belief, action));

}

};

return sampleSequence(startState, priorBelief, 'noAction');

};

Applying the POMDP agent model

Multi-arm Bandits

Multi-armed Bandits are an especially simple class of sequential decision problem. A Bandit problem has a single state and multiple actions (“arms”), where each arm has a distribution on rewards/utilities that is initially unknown. The agent has a finite time horizon and must balance exploration (i.e. learn about the reward distribution) with exploitation (obtain reward).

Bandits can be modeled as Reinforcement Learning problems, where the agent learns a good policy for an initially unknown MDP. This is the practical way to solve Bandits and the next chapter illustrates this approach. Here we model Bandits as POMDPs and use the code above to find the optimal policy for some toy Bandit problems2. (We choose a Bandit example to demonstrate the difficulty of exactly solving even the simplest POMDPs.)

In our examples, the arms are labeled with integers and arm has Bernoulli distributed rewards with parameter . In the first codebox (below), the true reward distribution, , is but the agent’s prior is uniform over and . So the agent’s only uncertainty is over .

Rather than implement everything in the codebox, we use the library webppl-agents. This includes functions for constructing a Bandit environment (makeBanditPOMDP), for constructing a POMDP agent (makePOMDPAgent) and for running the agent on the environment (simulatePOMDP). This chapter explains how to use webppl-agents. The Appendix includes a codebox with a full implementation of a POMDP agent on a Bandit problem.

///fold: displayTrajectory

// Takes a trajectory containing states and actions and returns one containing

// locs and actions, getting rid of 'start' and the final meaningless action.

var displayTrajectory = function(trajectory) {

var getPrizeAction = function(stateAction) {

var state = stateAction[0];

var action = stateAction[1];

return [state.manifestState.loc, action];

};

var prizesActions = map(getPrizeAction, trajectory);

var flatPrizesActions = _.flatten(prizesActions);

var actionsPrizes = flatPrizesActions.slice(1, flatPrizesActions.length - 1);

var printOut = function(n) {

print('\n Arm: ' + actionsPrizes[2*n] + ' -- Prize: '

+ actionsPrizes[2*n + 1]);

};

return map(printOut, _.range((actionsPrizes.length)*0.5));

};

///

// 1. Construct Bandit POMDP

// Reward distributions are Bernoulli

var getRewardDist = function(theta){

return Categorical({ vs:[0,1], ps: [1-theta, theta]});

}

// True reward distributions are [.7,.8].

var armToRewardDist = {

0: getRewardDist(.7),

1: getRewardDist(.8)

};

// But the agent's prior is uniform over [.7,.8] and [.7,.2].

var alternateArmToRewardDist = {

0: getRewardDist(.7),

1: getRewardDist(.2)

}

// Options for library function for Bandits. Number of trials = horizon.

var banditOptions = {

numberOfArms: 2,

armToPrizeDist: armToRewardDist,

numberOfTrials: 11,

numericalPrizes: true

};

var bandit = makeBanditPOMDP(banditOptions);

var startState = bandit.startState;

var world = bandit.world;

// 2. Construct POMDP agent

// Prior as described above and *latentState* is an implementation detail

// for the libraries implementation of POMDPs

var priorBelief = Infer({ model() {

var armToRewardDist = uniformDraw([armToRewardDist,

alternateArmToRewardDist]);

return extend(startState, { latentState: armToRewardDist });

}});

var utility = function(state, action) {

var reward = state.manifestState.loc;

return reward === 'start' ? 0 : reward;

};

var params = {

priorBelief,

utility,

alpha: 1000

};

var agent = makePOMDPAgent(params, bandit.world);

// 3. Simulate agent and return state-action pairs

var trajectory = simulatePOMDP(startState, world, agent, 'stateAction');

displayTrajectory(trajectory);

Solving Bandit problems using the simple dynamic approach of our POMDP agent does not blows up as the horizon (“number of trials”) and number of arms increase. The codebox below shows how runtime scales as a function of the number of trials. (This takes approximately 20 seconds to run.)

///fold: Construct world and agent priorBelief as above

var getRewardDist = function(theta){

return Categorical({ vs:[0,1], ps: [1-theta, theta]});

}

// True reward distributions are [.7,.8].

var armToRewardDist = {

0: getRewardDist(.7),

1: getRewardDist(.8)

};

// But the agent's prior is uniform over [.7,.8] and [.7,.2].

var alternateArmToRewardDist = {

0: getRewardDist(.7),

1: getRewardDist(.2)

}

var makeBanditWithNumberOfTrials = function(numberOfTrials) {

return makeBanditPOMDP({

numberOfTrials,

numberOfArms: 2,

armToPrizeDist: armToRewardDist,

numericalPrizes: true

});

};

var getPriorBelief = function(numberOfTrials){

return Infer({ model() {

var armToPrizeDist = uniformDraw([armToRewardDist,

alternateArmToRewardDist]);

return makeBanditStartState(numberOfTrials, armToPrizeDist);

}})

};

var baseParams = { alpha: 1000 };

///

// Simulate agent for a given number of Bandit trials

var getRuntime = function(numberOfTrials) {

var bandit = makeBanditWithNumberOfTrials(numberOfTrials);

var world = bandit.world;

var startState = bandit.startState;

var priorBelief = getPriorBelief(numberOfTrials)

var params = extend(baseParams, { priorBelief });

var agent = makeBanditAgent(params, bandit, 'belief');

var f = function() {

return simulatePOMDP(startState, world, agent, 'stateAction');

};

return timeit(f).runtimeInMilliseconds.toPrecision(3) * 0.001;

};

// Runtime as a function of number of trials

var numberOfTrialsList = _.range(15).slice(2);

var runtimes = map(getRuntime, numberOfTrialsList);

viz.line(numberOfTrialsList, runtimes);

Scaling is much worse in the number of arms. The following may take over a minute to run:

///fold:

var getRewardDist = function(theta){

return Categorical({ vs:[0,1], ps: [1-theta, theta]});

}

var makeArmToRewardDist = function(numberOfArms) {

return map(function(x) { return getRewardDist(0.8); }, _.range(numberOfArms));

};

var armToRewardDistSampler = function(numberOfArms) {

return map(function(x) { return uniformDraw([getRewardDist(0.2),

getRewardDist(0.8)]); },

_.range(numberOfArms));

};

var getPriorBelief = function(numberOfTrials, numberOfArms) {

return Infer({ model() {

var armToRewardDist = armToRewardDistSampler(numberOfArms);

return makeBanditStartState(numberOfTrials, armToRewardDist);

}});

};

var baseParams = {alpha: 1000};

///

var getRuntime = function(numberOfArms) {

var armToRewardDist = makeArmToRewardDist(numberOfArms);

var options = {

numberOfTrials: 5,

armToPrizeDist: armToRewardDist,

numberOfArms,

numericalPrizes: true

};

var numberOfTrials = options.numberOfTrials;

var bandit = makeBanditPOMDP(options);

var world = bandit.world;

var startState = bandit.startState;

var priorBelief = getPriorBelief(numberOfTrials, numberOfArms);

var params = extend(baseParams, { priorBelief });

var agent = makeBanditAgent(params, bandit, 'belief');

var f = function() {

return simulatePOMDP(startState, world, agent, 'stateAction');

};

return timeit(f).runtimeInMilliseconds.toPrecision(3) * 0.001;

};

// Runtime as a function of number of arms

var numberOfArmsList = [1, 2, 3];

var runtimes = map(getRuntime, numberOfArmsList);

viz.line(numberOfArmsList, runtimes);

Gridworld with observations

A person looking for a place to eat will not be fully informed about all local restaurants. This section extends the Restaurant Choice problem to represent an agent with uncertainty about which restaurants are open. The agent observes whether a restaurant is open by moving to one of the grid locations adjacent to the restaurant. If the restaurant is open, the agent can enter and receive utility.

The POMDP version of Restaurant Choice is built from the MDP version. States now have the form:

{manifestState: { ... }, latentState: { ... }}

The manifestState contains the features of the world that the agent always observes directly (and so always knows). This includes the remaining time and the agent’s location in the grid. The latentState contains features that are only observable in certain states. In our examples, latentState specifies whether each restaurant is open or closed. The transition function for the POMDP is the same as the MDP except that if a restaurant is closed the agent cannot transition to it.

The next two codeboxes use the same POMDP, where all restaurants are open but for Noodle. The first agent prefers the Donut Store and believes (falsely) that Donut South is likely closed. The second agent prefers Noodle and believes (falsely) that Noodle is likely open.

///fold:

var getPriorBelief = function(startManifestState, latentStateSampler){

return Infer({ model() {

return {

manifestState: startManifestState,

latentState: latentStateSampler()};

}});

};

var ___ = ' ';

var DN = { name : 'Donut N' };

var DS = { name : 'Donut S' };

var V = { name : 'Veg' };

var N = { name : 'Noodle' };

var grid = [

['#', '#', '#', '#', V , '#'],

['#', '#', '#', ___, ___, ___],

['#', '#', DN , ___, '#', ___],

['#', '#', '#', ___, '#', ___],

['#', '#', '#', ___, ___, ___],

['#', '#', '#', ___, '#', N ],

[___, ___, ___, ___, '#', '#'],

[DS , '#', '#', ___, '#', '#']

];

var pomdp = makeGridWorldPOMDP({

grid,

noReverse: true,

maxTimeAtRestaurant: 2,

start: [3, 1],

totalTime: 11

});

///

var utilityTable = {

'Donut N': 5,

'Donut S': 5,

'Veg': 1,

'Noodle': 1,

'timeCost': -0.1

};

var utility = function(state, action) {

var feature = pomdp.feature;

var name = feature(state.manifestState).name;

if (name) {

return utilityTable[name];

} else {

return utilityTable.timeCost;

}

};

var latent = {

'Donut N': true,

'Donut S': true,

'Veg': true,

'Noodle': false

};

var alternativeLatent = extend(latent, {

'Donut S': false,

'Noodle': true

});

var startState = {

manifestState: {

loc: [3, 1],

terminateAfterAction: false,

timeLeft: 11

},

latentState: latent

};

var latentStateSampler = function() {

return categorical([0.8, 0.2], [alternativeLatent, latent]);

};

var priorBelief = getPriorBelief(startState.manifestState, latentStateSampler);

var agent = makePOMDPAgent({ utility, priorBelief, alpha: 100 }, pomdp);

var trajectory = simulatePOMDP(startState, pomdp, agent, 'states');

var manifestStates = _.map(trajectory, _.property('manifestState'));

viz.gridworld(pomdp.MDPWorld, { trajectory: manifestStates });

Here is the agent that prefers Noodle and falsely belives that it is open:

///fold: Same world, prior, start state, and latent state as previous codebox

var getPriorBelief = function(startManifestState, latentStateSampler){

return Infer({ model() {

return {

manifestState: startManifestState,

latentState: latentStateSampler()

};

}});

};

var ___ = ' ';

var DN = { name : 'Donut N' };

var DS = { name : 'Donut S' };

var V = { name : 'Veg' };

var N = { name : 'Noodle' };

var grid = [

['#', '#', '#', '#', V , '#'],

['#', '#', '#', ___, ___, ___],

['#', '#', DN , ___, '#', ___],

['#', '#', '#', ___, '#', ___],

['#', '#', '#', ___, ___, ___],

['#', '#', '#', ___, '#', N ],

[___, ___, ___, ___, '#', '#'],

[DS , '#', '#', ___, '#', '#']

];

var pomdp = makeGridWorldPOMDP({

grid,

noReverse: true,

maxTimeAtRestaurant: 2,

start: [3, 1],

totalTime: 11

});

var latent = {

'Donut N': true,

'Donut S': true,

'Veg': true,

'Noodle': false

};

var alternativeLatent = extend(latent, {

'Donut S': false,

'Noodle': true

});

var startState = {

manifestState: {

loc: [3, 1],

terminateAfterAction: false,

timeLeft: 11

},

latentState: latent

};

var latentSampler = function() {

return categorical([0.8, 0.2], [alternativeLatent, latent]);

};

var priorBelief = getPriorBelief(startState.manifestState, latentSampler);

///

var utilityTable = {

'Donut N': 1,

'Donut S': 1,

'Veg': 3,

'Noodle': 5,

'timeCost': -0.1

};

var utility = function(state, action) {

var feature = pomdp.feature;

var name = feature(state.manifestState).name;

if (name) {

return utilityTable[name];

} else {

return utilityTable.timeCost;

}

};

var agent = makePOMDPAgent({ utility, priorBelief, alpha: 100 }, pomdp);

var trajectory = simulatePOMDP(startState, pomdp, agent, 'states');

var manifestStates = _.map(trajectory, _.property('manifestState'));

viz.gridworld(pomdp.MDPWorld, { trajectory: manifestStates });

When does it make sense to treat this Restaurant Choice problem as a POMDP? As with Bandits, if the problem we face is a fixed (but initially unknown) MDP, and we get many episodes in which to learn by trial and error, then Reinforcement Learning is a simple and scalable approach. If the MDP varies with every episode (e.g. the hidden state of whether a restaurant is open varies from day to day), then POMDP methods may work better. (Even in the case where the MDP is fixed, if the stakes are very high, it will be best to solve for the optimal POMDP policy.) Finally, if our goal is to model human planning, then POMDP models are worth considering as they are more sample efficient than RL techniques (and humans can often solve planning problems in very few tries).

The next chapter is on reinforcement learning, an approach which learns to solve an initially unknown MDP.

Appendix: Complete Implementation of POMDP agent for Bandits

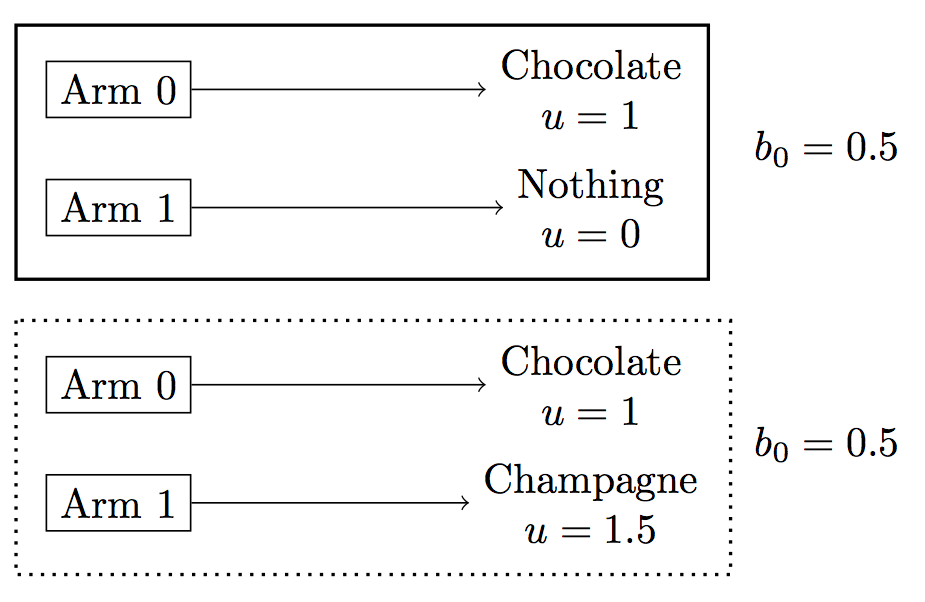

We apply the POMDP agent to a simplified variant of the Multi-arm Bandit Problem. In this variant, pulling an arm produces a prize deterministically. The agent begins with uncertainty about the mapping from arms to prizes and learns by trying the arms. In our example, there are only two arms. The first arm is known to have the prize “chocolate” and the second arm either has “champagne” or has no prize at all (“nothing”). See Figure 2 (below) for details.

Figure 2: Diagram for deterministic Bandit problem used in the codebox below. The boxes represent possible deterministic mappings from arms to prizes. Each prize has a reward/utility . On the right are the agent’s initial beliefs about the probability of each mapping. The true mapping (i.e. true latent state) has a solid outline.

In our implementation of this problem, the two arms are labeled “0” and “1” respectively. The action of pulling Arm0 is also labeled “0” (and likewise for Arm1). After taking action 0, the agent transitions to a state corresponding to the prize for Arm0 and the gets to observe this prize. States are Javascript objects that contain a property for counting down the time (as in the MDP case) as well as a prize property. States also contain the latent mapping from arms to prizes (called armToPrize) that determines how an agent transitions on pulling an arm.

// Pull arm0 or arm1

var actions = [0, 1];

// Use latent "armToPrize" mapping in state to

// determine which prize agent gets

var transition = function(state, action){

var newTimeLeft = state.timeLeft - 1;

return extend(state, {

prize: state.armToPrize[action],

timeLeft: newTimeLeft,

terminateAfterAction: newTimeLeft == 1

});

};

// After pulling an arm, agent observes associated prize

var observe = function(state){

return state.prize;

};

// Starting state specifies the latent state that agent tries to learn

// (In order that *prize* is defined, we set it to 'start', which

// has zero utilty for the agent).

var startState = {

prize: 'start',

timeLeft: 3,

terminateAfterAction:false,

armToPrize: { 0: 'chocolate', 1: 'champagne' }

};

Having illustrated our implementation of the POMDP agent and the Bandit problem, we put the pieces together and simulate the agent’s behavior. The makeAgent function is a simplified version of the library function makeBeliefAgent used throughout the rest of this tutorial3.

The Belief-Update Formula is implemented by updateBelief. Instead of hand-coding a Bayesian belief update, we simply use WebPPL’s built in inference primitives. This approach means our POMDP agent can do any kind of inference that WebPPL itself can do. For this tutorial, we use the inference function Enumerate, which captures exact inference over discrete belief spaces. By changing the inference function, we get a POMDP agent that does approximate inference and simulates their future selves as doing approximate inference. This inference could be over discrete or continuous belief spaces. (WebPPL includes Particle Filters, MCMC, and Hamiltonian Monte Carlo for differentiable models).

///fold: Bandit problem is defined as above

// Pull arm0 or arm1

var actions = [0, 1];

// Use latent "armToPrize" mapping in state to

// determine which prize agent gets

var transition = function(state, action){

var newTimeLeft = state.timeLeft - 1;

return extend(state, {

prize: state.armToPrize[action],

timeLeft: newTimeLeft,

terminateAfterAction: newTimeLeft == 1

});

};

// After pulling an arm, agent observes associated prize

var observe = function(state){

return state.prize;

};

// Starting state specifies the latent state that agent tries to learn

// (In order that *prize* is defined, we set it to 'start', which

// has zero utilty for the agent).

var startState = {

prize: 'start',

timeLeft: 3,

terminateAfterAction:false,

armToPrize: {0:'chocolate', 1:'champagne'}

};

///

// Defining the POMDP agent

// Agent params include utility function and initial belief (*priorBelief*)

var makeAgent = function(params) {

var utility = params.utility;

// Implements *Belief-update formula* in text

var updateBelief = function(belief, observation, action){

return Infer({ model() {

var state = sample(belief);

var predictedNextState = transition(state, action);

var predictedObservation = observe(predictedNextState);

condition(_.isEqual(predictedObservation, observation));

return predictedNextState;

}});

};

var act = dp.cache(

function(belief) {

return Infer({ model() {

var action = uniformDraw(actions);

var eu = expectedUtility(belief, action);

factor(1000 * eu);

return action;

}});

});

var expectedUtility = dp.cache(

function(belief, action) {

return expectation(

Infer({ model() {

var state = sample(belief);

var u = utility(state, action);

if (state.terminateAfterAction) {

return u;

} else {

var nextState = transition(state, action);

var nextObservation = observe(nextState);

var nextBelief = updateBelief(belief, nextObservation, action);

var nextAction = sample(act(nextBelief));

return u + expectedUtility(nextBelief, nextAction);

}

}}));

});

return { params, act, expectedUtility, updateBelief };

};

var simulate = function(startState, agent) {

var act = agent.act;

var updateBelief = agent.updateBelief;

var priorBelief = agent.params.priorBelief;

var sampleSequence = function(state, priorBelief, action) {

var observation = observe(state);

var belief = ((action === 'noAction') ? priorBelief :

updateBelief(priorBelief, observation, action));

var action = sample(act(belief));

var output = [[state, action]];

if (state.terminateAfterAction){

return output;

} else {

var nextState = transition(state, action);

return output.concat(sampleSequence(nextState, belief, action));

}

};

// Start with agent's prior and a special "null" action

return sampleSequence(startState, priorBelief, 'noAction');

};

//-----------

// Construct the agent

var prizeToUtility = {

chocolate: 1,

nothing: 0,

champagne: 1.5,

start: 0

};

var utility = function(state, action) {

return prizeToUtility[state.prize];

};

// Define true startState (including true *armToPrize*) and

// alternate possibility for startState (see Figure 2)

var numberTrials = 1;

var startState = {

prize: 'start',

timeLeft: numberTrials + 1,

terminateAfterAction: false,

armToPrize: { 0: 'chocolate', 1: 'champagne' }

};

var alternateStartState = extend(startState, {

armToPrize: { 0: 'chocolate', 1: 'nothing' }

});

// Agent's prior

var priorBelief = Categorical({

ps: [.5, .5],

vs: [startState, alternateStartState]

});

var params = { utility: utility, priorBelief: priorBelief };

var agent = makeAgent(params);

var trajectory = simulate(startState, agent);

print('Number of trials: ' + numberTrials);

print('Arms pulled: ' + map(second, trajectory));

You can change the agent’s behavior by varying numberTrials, armToPrize in startState or the agent’s prior. Note that the agent’s final arm pull is random because the agent only gets utility when leaving a state.

Footnotes

-

In the RL literature, the utility or reward function is often allowed to be stochastic. Our agent models assume that the agent’s utility function is deterministic. To represent environments with stochastic “rewards”, we treat the reward as a stochastic part of the environment (i.e. the world state). So in a Bandit problem, instead of the agent receiving a (stochastic) reward , they transition to a state to which they assign a fixed utility . (Why do we avoid stochastic utilities? One focus of this tutorial is inferring an agent’s preferences. The preferences are fixed over time and non-stochastic. We want to identify the agent’s utility function with their preferences). ↩

-

In the standard Bandit problem, there is a single unknown MDP characterized by the reward distribution of each arm. In a more challenging generalization, the agent faces a sequence of random Bandit problems that are drawn from some prior. If we treat a standard Bandit as a POMDP, we compute the Bayes optimal policy for the single Bandit and by doing so, we implicitly compute the optimal policy for a sequence of Bandits drawn from the same prior. This is analogous to finding the optimal policy for an MDP: the optimal policy covers every possible state, including those occurring with tiny probability. Model-free RL, by contrast, will focus on the states that are actually encountered in practice. ↩

-

One difference between the functions is that

makeAgentuses the global variablestransitionandobservation, instead of having aworldparameter. ↩