Bounded Agents-- Myopia for rewards and updates

Introduction

The previous chapter extended the MDP agent model to include exponential and hyperbolic discounting. The goal was to produce models of human behavior that capture a prominent bias (time inconsistency). As noted earlier humans are not just biased but also cognitively bounded. This chapter extends the POMDP agent to capture heuristics for planning that are sub-optimal but fast and frugal.

Reward-myopic Planning: the basic idea

Optimal planning is difficult because the best action now depends on the entire future. The optimal POMDP agent reasons backwards from the utility of its final state, judging earlier actions on whether they lead to good final states. With an infinite time horizon, an optimal agent must consider the expected utility of being in every possible state, including states only reachable after a very long duration.

Instead of explicitly optimizing for the entire future when taking an action, an agent can “myopically” optimize for near-term rewards. With a time-horizon of 1000 timesteps, a myopic agent’s first action might optimize for reward up to timestep . Their second action would optimize for rewards up to , and so on. Whereas the optimal agent computes a complete policy before the first timestep and then follows the policy, the “reward-myopic agent” computes a new myopic policy at each timestep, thus spreading out computation over the whole time-horizon and usually doing much less computation overall1.

The Reward-myopic agent succeeds when continually optimizing for the short-term produces good long-term performance. Often this fails: climbing a moutain can get progressively more exhausting and painful until the summit is finally reached. One patch for this problem is to provide the agent with fake short-term rewards that are a proxy for long-term expected utility. This is closely related to “reward shaping” in Reinforcement Learning refp:chentanez2004intrinsically.

Reward-myopic Planning: implementation and examples

The Reward-myopic agent takes the action that would be optimal if the time-horizon were steps into the future. The “cutoff” or “bound”, , will typically be much smaller than the time horizon for the decision problem.

Notice the similarity between Reward-myopic agents and hyperbolic discounting agents. Both agents make plans based on short-term rewards. Both revise these plans at every timestep. And the Naive Hyperbolic Discounter and Reward-myopic agents both have implicit models of their future selves that are incorrect. A major difference is that Reward-myopic planning is easy to make computationally fast. The Reward-myopic agent can be implemented using the concept of delay described in the previous chapter and the implementation is left as an exercise:

Exercise: Formalize POMDP and MDP versions of the Reward-myopic agent by modifiying the equations for the expected utility of state-action pairs or belief-state-action pairs. Implement the agent by modifying the code for the POMDP and MDP agents. Verify that the agent behaves sub-optimally (but more efficiently) on Gridworld and Bandit problems.

The Reward-myopic agent succeeds if good short-term actions produce good long-term consequences. In Bandit problems, elaborate long-terms plans are not needed to reach particular desirable future states. It turns out that a maximally Reward-myopic agent, who only cares about the immediate reward (), does well on Multi-arm Bandits provided they take noisy actions refp:kuleshov2014algorithms.

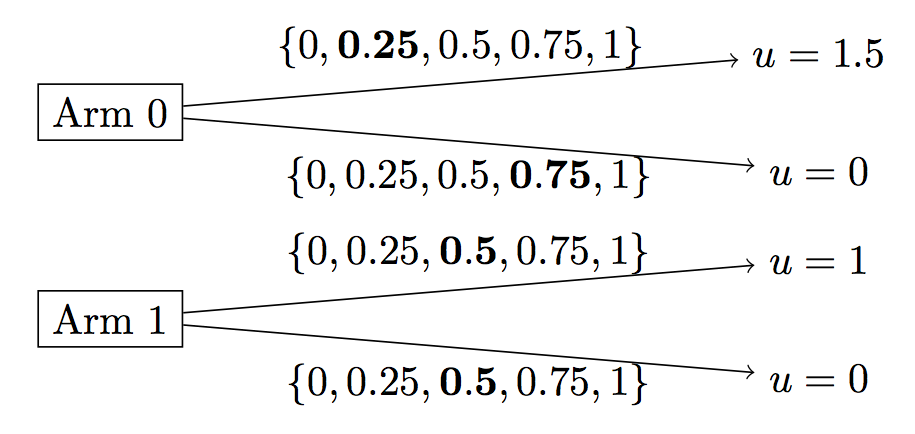

The next codeboxes show the performance of the Reward-myopic agent on Bandit problems. The first codebox is a two-arm Bandit problem, illustrated in Figure 1. We use a Reward-myopic agent with high softmax noise: and . The Reward-myopic agent’s average reward over 100 trials is close to the expected average reward given perfect knowledge of the arms.

Figure 1: Bandit problem. The curly brackets contain possible probabilities according to the agent’s prior (the bolded number is the true probability). For

arm0, the agent has a uniform prior on the values for the probability the arm yields the reward 1.5.

///fold: getUtility

var getUtility = function(state, action) {

var prize = state.manifestState.loc;

return prize === 'start' ? 0 : prize;

};

///

// Construct world: One bad arm, one good arm, 100 trials.

var trueArmToPrizeDist = {

0: Categorical({ vs: [1.5, 0], ps: [0.25, 0.75] }),

1: Categorical({ vs: [1, 0], ps: [0.5, 0.5] })

};

var numberOfTrials = 100;

var bandit = makeBanditPOMDP({

numberOfTrials,

numberOfArms: 2,

armToPrizeDist: trueArmToPrizeDist,

numericalPrizes: true

});

var world = bandit.world;

var startState = bandit.startState;

// Construct reward-myopic agent

// Arm0 is a mixture of [0,1.5] and Arm1 of [0,1]

var agentPrior = Infer({ model() {

var prob15 = uniformDraw([0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1]);

var prob1 = uniformDraw([0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1]);

var armToPrizeDist = {

0: Categorical({ vs: [1.5, 0], ps: [prob15, 1 - prob15] }),

1: Categorical({ vs: [1, 0], ps: [prob1, 1 - prob1] })

};

return makeBanditStartState(numberOfTrials, armToPrizeDist);

}});

var rewardMyopicBound = 1;

var alpha = 10; // noise level

var params = {

alpha,

priorBelief: agentPrior,

rewardMyopic: { bound: rewardMyopicBound },

noDelays: false,

discount: 0,

sophisticatedOrNaive: 'naive'

};

var agent = makeBanditAgent(params, bandit, 'beliefDelay');

var trajectory = simulatePOMDP(startState, world, agent, 'states');

var averageUtility = listMean(map(getUtility, trajectory));

print('Arm1 is best arm and has expected utility 0.5.\n' +

'So ideal performance gives average score of: 0.5 \n' +

'The average score over 100 trials for rewardMyopic agent: ' +

averageUtility);

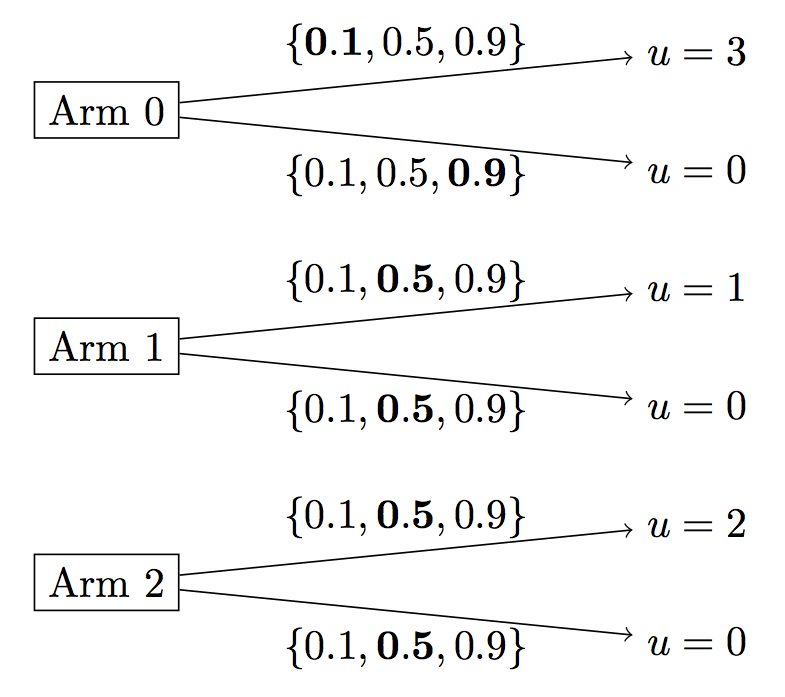

The next codebox is a three-arm Bandit problem show in Figure 2. Given the agent’s prior, arm0 has the highest prior expectation. So the agent will try that before exploring other arms. We show the agent’s actions and their average score over 40 trials.

Figure 2: Bandit problem where

arm0has highest prior expectation for the agent but wherearm2is actually the best arm. (This may take a while to run.)

// agent is same as above: bound=1, alpha=10

///fold:

var rewardMyopicBound = 1;

var alpha = 10; // noise level

var params = {

alpha: 10,

rewardMyopic: { bound: rewardMyopicBound },

noDelays: false,

discount: 0,

sophisticatedOrNaive: 'naive'

};

var getUtility = function(state, action) {

var prize = state.manifestState.loc;

return prize === 'start' ? 0 : prize;

};

///

var trueArmToPrizeDist = {

0: Categorical({ vs: [3, 0], ps: [0.1, 0.9] }),

1: Categorical({ vs: [1, 0], ps: [0.5, 0.5] }),

2: Categorical({ vs: [2, 0], ps: [0.5, 0.5] })

};

var numberOfTrials = 40;

var bandit = makeBanditPOMDP({

numberOfArms: 3,

armToPrizeDist: trueArmToPrizeDist,

numberOfTrials,

numericalPrizes: true

});

var world = bandit.world;

var startState = bandit.startState;

var agentPrior = Infer({ model() {

var prob3 = uniformDraw([0.1, 0.5, 0.9]);

var prob1 = uniformDraw([0.1, 0.5, 0.9]);

var prob2 = uniformDraw([0.1, 0.5, 0.9]);

var armToPrizeDist = {

0: Categorical({ vs: [3, 0], ps: [prob3, 1 - prob3] }),

1: Categorical({ vs: [1, 0], ps: [prob1, 1 - prob1] }),

2: Categorical({ vs: [2, 0], ps: [prob2, 1 - prob2] })

};

return makeBanditStartState(numberOfTrials, armToPrizeDist);

}});

var params = extend(params, { priorBelief: agentPrior });

var agent = makeBanditAgent(params, bandit, 'beliefDelay');

var trajectory = simulatePOMDP(startState, world, agent, 'stateAction');

print("Agent's first 20 actions (during exploration phase): \n" +

map(second,trajectory.slice(0,20)));

var averageUtility = listMean(map(getUtility, map(first,trajectory)));

print('Arm2 is best arm and has expected utility 1.\n' +

'So ideal performance gives average score of: 1 \n' +

'The average score over 40 trials for rewardMyopic agent: ' +

averageUtility);

Myopic Updating: the basic idea

The Reward-myopic agent ignores rewards that occur after its myopic cutoff . By contrast, an “Update-myopic agent”, takes into account all future rewards but ignores the value of belief updates that occur after a cutoff. Concretely, the agent at time assumes they can only explore (i.e. update beliefs from observations) up to some cutoff point steps into the future, after which they just exploit without updating beliefs. In reality, the agent continues to update after time . The Update-myopic agent, like the Naive hyperbolic discounter, has an incorrect model of their future self.

Myopic updating is optimal for certain special cases of Bandits and has good performance on Bandits in general refp:frazier2008knowledge. It also provides a good fit to human performance in Bernoulli Bandits refp:zhang2013forgetful.

Myopic Updating: applications and limitations

Myopic Updating has been studied in Machine Learning refp:gonzalez2015glasses and Operations Research refp:ryzhov2012knowledge. In most cases, the cutoff point after which the agent assumes himself to exploit is set to . This results in a scalable, analytically tractable optimization problem: pull the arm that maximizes the expected value of future exploitation given you pulled that arm. This “future exploitation” means that you pick the arm that is best in expectation for the rest of time.

We’ve presented Bandit problems with a finite number of uncorrelated arms. Myopic Updating also works for generalized Bandit Problems: e.g. when rewards are correlated or continuous and in the setting of “Bayesian Optimization” where instead of a fixed number of arms the goal is to optimize a high-dimensional real-valued function.

Myopic Updating does not work well for POMDPs in general. Suppose you are looking for a good restaurant in a foreign city. A good strategy is to walk to a busy street and then find the busiest restaurant. If reaching the busy street takes longer than the myopic cutoff , then an Update-myopic agent won’t see value in this plan. We present a concrete example of this problem below (“Restaurant Search”). This example highlights a way in which Bandit problems are an especially simple POMDP. In a Bandit problem, every aspect of the unknown latent state can be queried at any timestep (by pulling the appropriate arm). So even the Myopic Agent with is sensitive to the information value of every possible observation that the POMDP can yield2.

Myopic Updating: formal model

Myopic Updating only makes sense in the context of an agent that is capable of learning from observations (i.e. in the POMDP rather than MDP setting). So our goal is to generalize our agent model for solving POMDPs to a Myopic Updating with .

Exercise: Before reading on, modify the equations defining the POMDP agent in order to generalize the agent model to include Myopic Updating. The optimal POMDP agent will be the special case when .

To extend the POMDP agent to the Update-myopic agent, we use the idea of delays from the previous chapter. These delays are not used to evaluate future rewards (as any discounting agent would use them). They are used to determine how future actions are simulated. If the future action occurs when delay exceeds cutoff point , then the simulated future self does not do a belief update before taking the action. (This makes the Update-myopic agent analogous to the Naive agent: both simulate the future action by projecting the wrong delay value onto their future self).

We retain the notation from the definition of the POMDP agent and skip directly to the equation for the expected utility of a state, which we modify for the Update-myopic agent with cutoff point :

where:

-

and

-

is the softmax action the agent takes given new belief

-

the new belief state is defined as:

where if < and otherwise.

The key change from POMDP agent is the definition of . The Update-myopic agent assumes his future self (after the cutoff ) updates only on his last action and not on observation . For example, in a deterministic Gridworld the future self would keep track of his locations (as his location depends deterministically on his actions) but wouldn’t update his belief about hidden states.

The implementation of the Update-myopic agent in WebPPL is a direct translation of the definition provided above.

Exercise: Modify the code for the POMDP agent to represent an Update-myopic agent. See this codebox or this library script.

Myopic Updating for Bandits

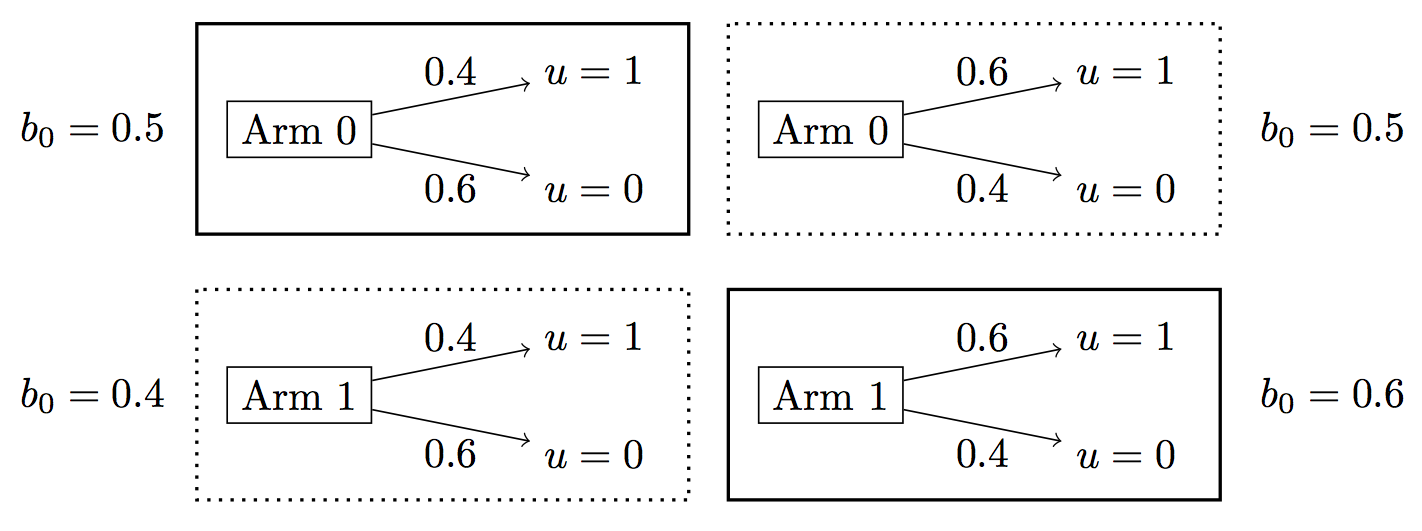

The Update-myopic agent performs well on a variety of Bandit problems. The following codeboxes compare the Update-myopic agent to the Optimal POMDP agent on binary, two-arm Bandits (see the specific example in Figure 3).

Figure 3: Bandit problem. The agent’s prior includes two hypotheses for the rewards of each arm, with the prior probability of each labeled to the left and right of the boxes. The priors on each arm are independent and so there are four hypotheses overall. Boxes with actual rewards have a bold border.

// Helper functions for Bandits:

///fold:

// HELPERS FOR CONSTRUCTING AGENT

var baseParams = {

alpha: 1000,

noDelays: false,

sophisticatedOrNaive: 'naive',

updateMyopic: { bound: 1 },

discount: 0

};

var getParams = function(agentPrior) {

var params = extend(baseParams, { priorBelief: agentPrior });

return extend(params);

};

var getAgentPrior = function(numberOfTrials, priorArm0, priorArm1) {

return Infer({ model() {

var armToPrizeDist = { 0: priorArm0(), 1: priorArm1() };

return makeBanditStartState(numberOfTrials, armToPrizeDist);

}});

};

// HELPERS FOR CONSTRUCTING WORLD

// Possible distributions for arms

var probably0Dist = Categorical({ vs: [0, 1], ps: [0.6, 0.4] });

var probably1Dist = Categorical({ vs: [0, 1], ps: [0.4, 0.6] });

// Construct Bandit POMDP

var getBandit = function(numberOfTrials){

return makeBanditPOMDP({

numberOfArms: 2,

armToPrizeDist: { 0: probably0Dist, 1: probably1Dist },

numberOfTrials: numberOfTrials,

numericalPrizes: true

});

};

var getUtility = function(state, action) {

var prize = state.manifestState.loc;

return prize === 'start' ? 0 : prize;

};

// Get score for a single episode of bandits

var score = function(out) {

return listMean(map(getUtility, out));

};

///

// Agent prior on arm rewards

// Possible distributions for arms

var probably0Dist = Categorical({ vs: [0, 1], ps: [0.6, 0.4] });

var probably1Dist = Categorical({ vs: [0, 1], ps: [0.4, 0.6] });

// True latentState:

// arm0 is probably0Dist, arm1 is probably1Dist (and so is better)

// Agent prior on arms: arm1 (better arm) has higher EV

var priorArm0 = function() {

return categorical([0.5, 0.5], [probably1Dist, probably0Dist]);

};

var priorArm1 = function(){

return categorical([0.6, 0.4], [probably1Dist, probably0Dist]);

};

var runAgent = function(numberOfTrials, optimal) {

// Construct world and agents

var bandit = getBandit(numberOfTrials);

var world = bandit.world;

var startState = bandit.startState;

var prior = getAgentPrior(numberOfTrials, priorArm0, priorArm1);

var agentParams = getParams(prior);

var agent = makeBanditAgent(agentParams, bandit,

optimal ? 'belief' : 'beliefDelay');

return score(simulatePOMDP(startState, world, agent, 'states'));

};

// Run each agent 10 times and take average of scores

var means = map(function(optimal) {

var scores = repeat(10, function(){ return runAgent(5,optimal); });

var st = optimal ? 'Optimal: ' : 'Update-Myopic: ';

print(st + 'Mean scores on 10 repeats of 5-trial bandits\n' + scores);

return listMean(scores);

}, [true, false]);

print('Overall means for [Optimal,Update-Myopic]: ' + means);

Exercise: The above codebox shows that performance for the two agents is similar. Try varying the priors and the

armToPrizeDistand verify that performance remains similar. How would you provide stronger empirical evidence that the two algorithms are equivalent for this problem?

The following codebox computes the runtime for Update-myopic and Optimal agents as a function of the number of Bandit trials. (This takes a while to run.) We see that the Update-myopic agent has better scaling even on a small number of trials. Note that neither agent has been optimized for Bandit problems.

Exercise: Think of ways to optimize the Update-myopic agent with for binary Bandit problems.

///fold: Similar helper functions as above codebox

// HELPERS FOR CONSTRUCTING AGENT

var baseParams = {

alpha: 1000,

noDelays: false,

sophisticatedOrNaive: 'naive',

updateMyopic: { bound: 1 },

discount: 0

};

var getParams = function(agentPrior){

var params = extend(baseParams, { priorBelief: agentPrior });

return extend(params);

};

var getAgentPrior = function(numberOfTrials, priorArm0, priorArm1){

return Infer({ model() {

var armToPrizeDist = { 0: priorArm0(), 1: priorArm1() };

return makeBanditStartState(numberOfTrials, armToPrizeDist);

}});

};

// HELPERS FOR CONSTRUCTING WORLD

// Possible distributions for arms

var probably1Dist = Categorical({ vs: [0, 1], ps: [0.4, 0.6] });

var probably0Dist = Categorical({ vs: [0, 1], ps: [0.6, 0.4] });

// Construct Bandit POMDP

var getBandit = function(numberOfTrials) {

return makeBanditPOMDP({

numberOfArms: 2,

armToPrizeDist: { 0: probably0Dist, 1: probably1Dist },

numberOfTrials,

numericalPrizes: true

});

};

var getUtility = function(state, action) {

var prize = state.manifestState.loc;

return prize === 'start' ? 0 : prize;

};

// Get score for a single episode of bandits

var score = function(out) {

return listMean(map(getUtility, out));

};

// Agent prior on arm rewards

// Possible distributions for arms

var probably0Dist = Categorical({ vs: [0, 1], ps: [0.6, 0.4] });

var probably1Dist = Categorical({ vs: [0, 1], ps: [0.4, 0.6] });

// True latentState:

// arm0 is probably0Dist, arm1 is probably1Dist (and so is better)

// Agent prior on arms: arm1 (better arm) has higher EV

var priorArm0 = function() {

return categorical([0.5, 0.5], [probably1Dist, probably0Dist]);

};

var priorArm1 = function(){

return categorical([0.6, 0.4], [probably1Dist, probably0Dist]);

};

var runAgents = function(numberOfTrials) {

// Construct world and agents

var bandit = getBandit(numberOfTrials);

var world = bandit.world;

var startState = bandit.startState;

var agentPrior = getAgentPrior(numberOfTrials, priorArm0, priorArm1);

var agentParams = getParams(agentPrior);

var optimalAgent = makeBanditAgent(agentParams, bandit, 'belief');

var myopicAgent = makeBanditAgent(agentParams, bandit, 'beliefDelay');

// Get average score across totalTime for both agents

var runOptimal = function() {

return score(simulatePOMDP(startState, world, optimalAgent, 'states'));

};

var runMyopic = function() {

return score(simulatePOMDP(startState, world, myopicAgent, 'states'));

};

var optimalDatum = {

numberOfTrials,

runtime: timeit(runOptimal).runtimeInMilliseconds*0.001,

agentType: 'optimal'

};

var myopicDatum = {

numberOfTrials,

runtime: timeit(runMyopic).runtimeInMilliseconds*0.001,

agentType: 'myopic'

};

return [optimalDatum, myopicDatum];

};

///

// Compute runtime as # Bandit trials increases

var totalTimeValues = _.range(9).slice(2);

print('Runtime in s for [Optimal, Myopic] agents:');

var runtimeValues = _.flatten(map(runAgents, totalTimeValues));

viz.line(runtimeValues, { groupBy: 'agentType' });

Myopic Updating for the Restaurant Search Problem

The Update-myopic agent assumes they will not update beliefs after the bound and so does not make plans that depend on learning something after the bound.

We illustrate this limitation with a new problem:

Restaurant Search: You are looking for a good restaurant in a foreign city without the aid of a smartphone. You know the quality of some restaurants already and you are uncertain about the others. If you walk right up to a restaurant, you can tell its quality by seeing how busy it is inside. You care about the quality of the restaurant and about minimizing the time spent walking.

How does the Update-myopic agent fail? Suppose that a few blocks from agent is a great restaurant next to a bad restaurant and the agent doesn’t know which is which. If the agent checked inside each restaurant, they would pick out the great one. But if they are Update-myopic, they assume they’d be unable to tell between them.

The codebox below depicts a toy version of this problem in Gridworld. The restaurants vary in quality between 0 and 5. The agent knows the quality of Restaurant A and is unsure about the other restaurants. One of Restaurants D and E is great and the other is bad. The Optimal POMDP agent will go right up to each restaurant and find out which is great. The Update-myopic agent, with low enough bound , will either go to the known good restaurant A or investigate one of the restaurants that is closer than D and E.

var pomdp = makeRestaurantSearchPOMDP();

var world = pomdp.world;

var makeUtilityFunction = pomdp.makeUtilityFunction;

var startState = pomdp.startState;

var agentPrior = Infer({ model() {

var rewardD = uniformDraw([0,5]); // D is bad or great (E is opposite)

var latentState = {

A: 3,

B: uniformDraw(_.range(6)),

C: uniformDraw(_.range(6)),

D: rewardD,

E: 5 - rewardD

};

return {

manifestState: pomdp.startState.manifestState,

latentState

};

}});

// Construct optimal agent

var params = {

utility: makeUtilityFunction(-0.01), // timeCost is -.01

alpha: 1000,

priorBelief: agentPrior

};

var agent = makePOMDPAgent(params, world);

var trajectory = simulatePOMDP(pomdp.startState, world, agent, 'states');

var manifestStates = _.map(trajectory, _.property('manifestState'));

print('Quality of restaurants: \n' +

JSON.stringify(pomdp.startState.latentState));

viz.gridworld(pomdp.mdp, { trajectory: manifestStates });

Exercise: The codebox below shows the behavior the Update-myopic agent. Try different values for the

myopicBoundparameter. For values in , explain the behavior of the Update-myopic agent.

///fold: Construct world and agent prior as above

var pomdp = makeRestaurantSearchPOMDP();

var world = pomdp.world;

var makeUtilityFunction = pomdp.makeUtilityFunction;

var agentPrior = Infer({ model() {

var rewardD = uniformDraw([0,5]); // D is bad or great (E is opposite)

var latentState = {

A: 3,

B: uniformDraw(_.range(6)),

C: uniformDraw(_.range(6)),

D: rewardD,

E: 5 - rewardD

};

return {

manifestState: pomdp.startState.manifestState,

latentState

};

}});

///

var myopicBound = 1;

var params = {

utility: makeUtilityFunction(-0.01),

alpha: 1000,

priorBelief: agentPrior,

noDelays: false,

discount: 0,

sophisticatedOrNaive: 'naive',

updateMyopic: { bound: myopicBound }

};

var agent = makePOMDPAgent(params, world);

var trajectory = simulatePOMDP(pomdp.startState, world, agent, 'states');

var manifestStates = _.map(trajectory, _.property('manifestState'));

print('Rewards for each restaurant: ' +

JSON.stringify(pomdp.startState.latentState));

print('Myopic bound: ' + myopicBound);

viz.gridworld(pomdp.mdp, { trajectory: manifestStates });

Next chapter: Joint inference of biases and preferences I

Footnotes

-

If optimal planning is super-linear in the time-horizon, the Reward-myopic agent will do less computation overall. The Reward-myopic agent only considers states or belief-states that it actually enters or that it gets close to, while the Optimal approach considers every possible state or belief-state. ↩

-

The Update-myopic agent incorrectly models his future self, by assuming he ceases to update after cutoff point . This incorrect “self-modeling” is also a property of model-free RL agents. For example, a Q-learner’s estimation of expected utilities for states ignores the fact that the Q-learner will randomly explore with some probability. SARSA, on the other hand, does take its random exploration into account when computing this estimate. But it doesn’t model the way in which its future exploration behavior will make certain actions useful in the present (as in the example of finding a restaurant in a foreign city). ↩